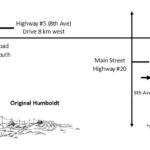

The Original Humboldt site is a scenic 80 acres of land located an 11 kilometer drive southwest of Humboldt where the original Humboldt Telegraph Station was built in 1878. The significance of the land is multifaceted, as it played an important role in the Canadian story of communications, transportation, the 1885 North West Resistance, relations with First Nations and Métis people, and the settlement of Saskatchewan. Groomed walking trails are available during the summer for visitors to walk out onto the land.

The site includes a public access area with seven storyboards telling the story of the site. In 2012, a Flag Ceremony was held with members of the Governor General’s Horse Guards at the military encampment area of the site, where Lt. Colonel Denison had stationed his regiment. The flag of the Governor General’s Horse Guards as well as the Union Jack were raised to mark the first time in 127 years that the Guards stood on the ground of their camp during the 1885 NorthWest Resistance. Two new art installations were created in 2013 to further commemorate the Original Humboldt site. A metal log cabin was created by Murray Cook, and a metal Red River Cart by Don Wilkins. A Métis flag was presented in the summer of 2014 by Robert Doucette, President of the Métis Nation of Saskatchewan, which is flown beside the Red River Cart. In 2016, a replica of the telegraph line was added to the site, and a native grass restoration project is underway to return the site to closer to its original form.

During the Resistance, federal troops arrived at the Humboldt telegraph station site under Lt. Colonel George Denison, awaiting orders from General Middleton. Denison noted that Humboldt was the end of the telegraph line, and the station played a very important part in communications during the Resistance. General Middleton sent messages to Humboldt via soldiers on horseback which Denison transmitted to Ottawa.

On March 23, 1885, the Winnipeg Daily News reported that “the reported uprising of Riel at Carlton, announced by dispatches from Humboldt, N.W.T., beyond which the lines have been cut, is causing great excitement… […] the telegraph wires have been cut northwest of Humboldt, thereby cutting off communication and necessitating the carrying of messages on horseback.”

Whitecap, the Dakota Sioux chief from Moose Woods, was held at the Original Humboldt site as a government prisoner after the fall of Batoche. He would be charged with treason-felony since he had not only been present at Métis headquarters during the fighting but was also the only Indian member of Louis Riel’s governing council. At his Regina trial on 18 September 1885, Whitecap had a white witness, the Dakota-speaking Gerald Willoughby of Saskatoon. Willoughby testified that the chief and his band had been forcibly taken from their reserve to Batoche by a large Métis force in early April and that the citizens of Saskatoon were helpless to stop it. He also described Whitecap as a loyal Indian who was always a welcome guest in homes throughout the district.

This testimony saved Whitecap from probable conviction. In fact, according to the surviving Department of Justice notes about the trial, the Crown prosecutor privately acknowledged that Whitecap was at Batoche against his will. The jury came to the same conclusion – after deliberating for only fifteen minutes, it returned with a verdict of not guilty. Judge Richardson, who normally lectured the accused before passing sentence, seemed surprised by the acquittal and pronounced simply, “You are now a free man again.”

Thanks to Bill Waiser, Department of History, University of Saskatchewan for the information on Chief Whitecap.

After the battle, the troops left Humboldt on July 9, 1885. Denison wrote in his book Soldiering in Canada: Recollections and Experiences, published in 1901: “We left Humboldt on July 9th, on a dull morning. The column consisted of the Body Guard and the provisional battalion, made up from the 12th York Rangers and the 35th Simcoe Foresters, under the command of Lieut-Colonel W. E. O’Brien. These two corps marched so well that I dubbed them my ‘foot cavalry.’ We left Humboldt at 8 a.m. on July 9th, and arrived at Fort Qu’Appelle at 11 a.m. on the 13th; a distance of about one hundred and forty miles, in four days and three hours.